Documenting Family Connections to the Boston Tea Party hero

This article was originally published in the Fall 2023 edition of American Ancestors magazine (Vol. 24, No. 3). Members of American Ancestors can access the full issue in our magazine archive. Not yet a member? Join Today

by Kristin Harris

The nineteenth century saw a rising interest in recording and celebrating connections to Revolutionary War events, including the Boston Tea Party. Many of the participants and descendants took pride in their ties to this historic event, passing family lore to subsequent generations. Tea Party–related accounts and anecdotes appeared in published histories and genealogies, as well as in private and institutional papers.

Stories of the patriots who took part in the events of December 16, 1773, have been saved and disseminated in various ways over time, as the examples below illustrate.

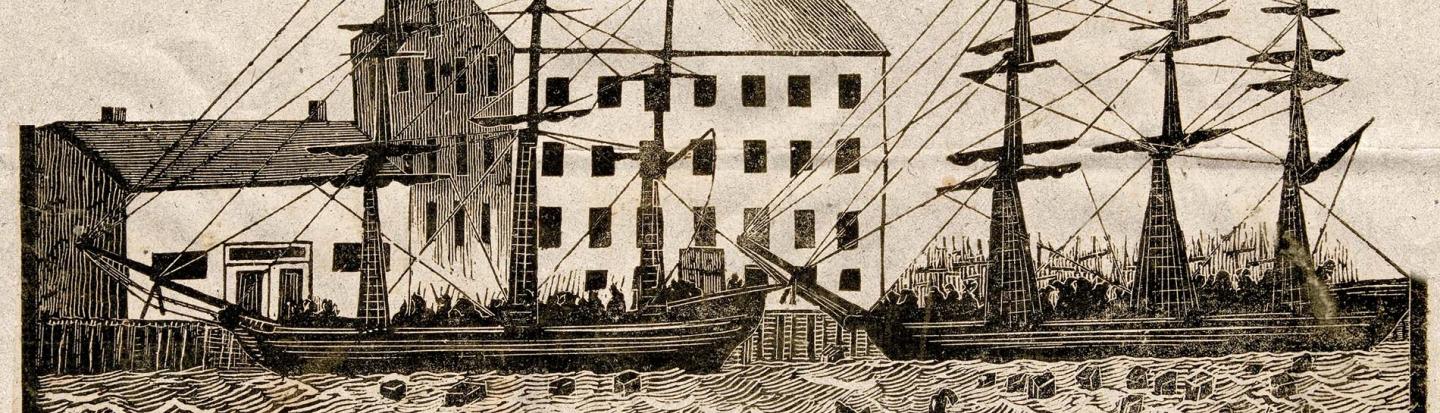

Top: The Boston Tea Party, 18th century. Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery.

Nathaniel Bradlee was born in Boston on February 16, 1746, one of twelve children of Samuel and Mary (Andrus) Bradlee. The Revolutionary War activities of Nathaniel and three of his brothers were documented by Samuel Bradlee Doggett, a great-grandson of Nathaniel, in his 1878 History of the Bradlee Family.1

A longer and more colorful description is in Francis S. Drake’s 1884 Tea Leaves, another key resource for documenting Tea Party participants. The “biographical notice” for the four Bradlee brothers includes this account, supplied by Samuel Bradlee Doggett: “Their sister, Sarah, assisted her husband, John Fulton, and her brothers, to disguise themselves, having made preparations for the emergency a day or two beforehand, and afterwards followed them to the wharf, and saw the tea thrown into the dock. Soon returning, she had hot water in readiness for them when they arrived, and assisted in removing the paint from their faces. As the story goes, before they could change their clothes, a British officer looked in to see if the young men were at home, having a suspicion that they were in the tea business. He found them in bed, and to all appearance asleep, they having slipped into bed without removing their ‘toggery,’ and feigning sleep. The officer departed satisfied.”3

On April 18, 1872, Edmund F. Slafter, Corresponding Secretary of New England Historic Genealogical Society (American Ancestors), wrote to member George Mountfort, requesting that he submit information “for permanent record to be deposited in the archives.”4

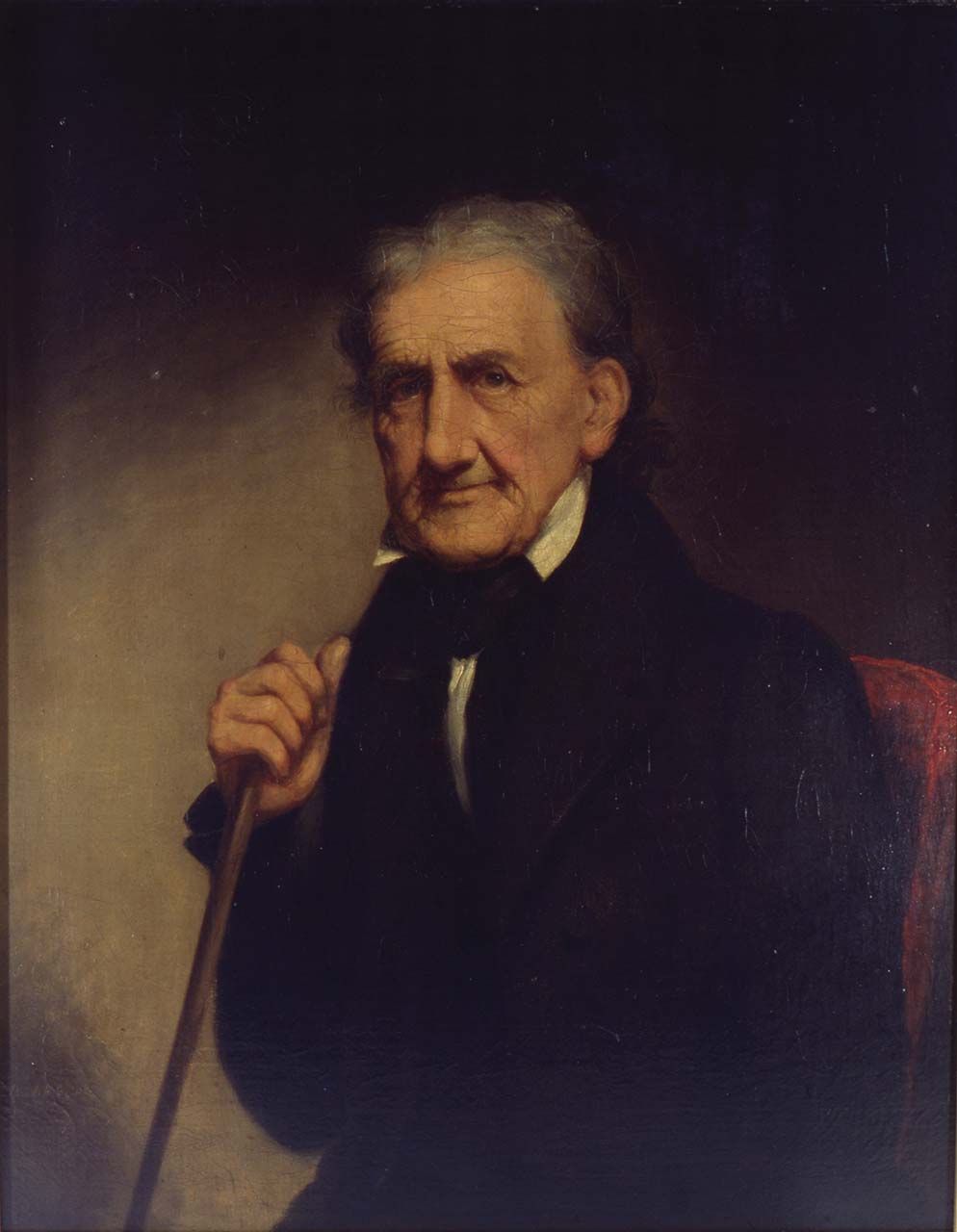

Born in Boston on March 16, 1798, George was first a clerk in the counting house of John Hancock, nephew of the well-known Revolutionary leader and Massachusetts governor. A business owner, freemason, diplomat, and historian—and clearly aware of the importance of preserving his family history—George became a Corresponding Member of American Ancestors in October 1855 and a Resident Member in 1862.5

In the papers he sent to American Ancestors, George recorded what he knew about his earlier ancestors, including his immigrant great-great-grandfather Edmund Mountfort, who arrived in Boston from London on the Providence in 1656. Writing in 1872, nearly a century after the opening events of the War for Independence, might have caused George to particularly reflect on the contributions of his father, Joseph Mountfort, who was born in Boston on February 5, 1750.6 George described Joseph as “one of the famous ‘Tea Party’ of December 16, 1773. Also a zealous patriot throughout the Revolution.”7

Joseph Mountfort participated in numerous exploits during the War for Independence—he “was in several terrible sea engagements, was thrice taken prisoner, and on one occasion, with sixteen others, broke from Mill prison [in Plymouth, England], and in an open boat, crossed the channel of England and France, and returned to Boston.”8 Given that Joseph went on to experience so many dramatic events while serving in the military, it is noteworthy that George mentioned his father’s participation in the Boston Tea Party. And perhaps Joseph Mountfort’s zeal for the patriot cause was most clearly proved by his presence at Griffin’s Wharf on that December night in 1773.

Today, as its 250th anniversary approaches, we at the Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum see a renewed interest in documenting and preserving tales of participation in the Tea Party.

In 2018, our organization began a new program with the aim of making Tea Party connections more visible. The first commemorative markers were placed at the graves of fifteen known participants at Boston’s Central Burying Ground. This inaugural event marked the beginning of the Boston Tea Party Participant Marker Project, a partnership between the Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum and Revolution 250. The goal is to place commemorative markers at the graves of as many known participants as possible before the 250th anniversary on December 16, 2023.

After years of perseverance and research, 110 markers have been placed at the graves of participants all over New England, and in New York, Michigan, and Ohio. We hope to place markers in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Paris, and locate the remaining graves in New England before the anniversary. (A list of markers can be viewed on the Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum website.) At these ceremonies held around the nation our staff members have met countless descendants, local historians, and town officials, and seen firsthand the continued impact and importance of preserving Tea Party history.

Through the marker project, we recently identified a previously unrecognized participant. On July 9, 2022, our Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum team traveled to Bantam, Connecticut, to place a marker for Elisha Horton. At the ceremony, we met John Lyman Cox, who, we would learn, was a descendant of Boston Tea Party participant Brevet Brigadier General Michael Jackson. John Cox’s aunt had recently died at 99 and he inherited four boxes of family records. John presented the team with a copy of a letter written by Michael Jackson’s son Ebenezer Jackson, to his son, Ebenezer Jackson, Jr.

Dated May 7, 1823, the letter was written twelve years before the 1835 publication of Traits of the Tea Party, a well-known biography of participant George Robert Twelves Hewes that contained a list of Tea Party participants. Although this list is considered by many to be the most definitive historical record of those involved in the Boston Tea Party, the author acknowledged that “of course it is not complete.”9 Michael Jackson was not listed in this book or in Tea Leaves.

To learn more, I visited the Massachusetts Historical Society to view the Jackson family papers and found additional copies of the letter. By researching muster rolls and pensions I corroborated many of the details Ebenezer Jackson provided. By conferring with our Boston Tea Party Descendants Program partners at American Ancestors, we determined that the account was sound, and it was highly likely that Michael Jackson was indeed on Griffin’s Wharf that night.

Born in Newton, Massachusetts, on December 18, 1734, Michael Jackson was a tanner who learned his trade from his father, also named Michael Jackson. The oldest child in his family, Jackson possessed an independent spirit and a sense of duty. He enrolled in a Massachusetts provincial regiment as a youth and eventually became a subaltern officer. Early in the French and Indian War, when the French were trying to drive the British out of Canada, Jackson enlisted in the King’s Army as a lieutenant. His service included the 1758 siege of Louisbourg and the Ticonderoga Campaign of 1758–59, and he was present for the capture of Quebec in 1759. After the Seven Years’ War ended and Jackson returned home to his family, he was a member of the Minute Men of Newton.

In March of 1773, when news of the Tea Act reached Massachusetts, Jackson served on a committee to “confer with the inhabitants of the town, as to the expediency of leaving off buying, selling or using any India Tea”10—meaning East India Company tea. Six months later, Jackson’s actions went well beyond serving on a committee. The relevant portion of Ebenezer Jackson’s 1823 letter was paraphrased in a Jackson genealogy: “At Newton Lieutenant Michael Jackson II, with several of his kin and many townsmen, similarly garbed [in disguises], hastily mounted their horses, galloped into Boston and to the harbor, where they joined the crowd, raided the ships, and dumped nearly ten thousand pounds’ worth of tea into the water.”11 Jackson’s story echoes others who were at the Boston Tea Party. Due to his storied military record, his years of involvement in the local militia, and his role with the tea committee in Newton, Jackson likely received trusted information, as did others in towns surrounding Boston, and made the journey to Griffin’s Wharf on December 16, 1773.

On April 19, 1775, Michael Jackson commanded the Newton Minute Men, which marched to Concord once the alarm was sounded, and exchanged shots with British soldiers. The Minute Men kept on the heels of the British as they retreated back through Cambridge to Boston.12 Jackson served in leadership positions for the remainder of the war, and was eventually promoted to Brevet Brigadier General while in command of the 8th Massachusetts Regiment. In November 1783, he was honorably discharged with the rest of the Continental Army.

On August 2, 2022, John and his brother Michael joined representatives from the Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum, Revolution 250, Historic Newton, and the town of Newton to officially commemorate General Michael Jackson as a participant in the Boston Tea Party with a marker at his gravesite. Due to the family’s outreach to us at the Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum and subsequent research in family papers and genealogies, John and Michael Cox were able to resolve the longstanding family question about their ancestor’s role in the Boston Tea Party.

Today the Boston Tea Party continues to resonate with Americans—and people all over the world. The memory of this historic event is kept alive in a variety of ways, through histories, images, artifacts, museum exhibits, monuments, markers, and genealogical connections.

As a way to create and strengthen these family history legacies, the Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum and American Ancestors launched the Boston Tea Party Descendants Program in March 2023. Part of a series of programming and initiatives to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party, this program aims to help descendants preserve their Revolutionary family ties in the first collaborative online genealogical platform focused solely on the Boston Tea Party. An ambitious project, the online platform is still under construction, and our goal is to launch access to the site by December 2023.We hope this program will help people engage with their Boston Tea Party family history in new ways, and increase knowledge of participants and their descendants.

Both the Boston Tea Party Participant Marker Program and the Boston Tea Party Descendants Program help extend the legacy of the Tea Party. Whenever researchers, family members, or the general public delve into this shared American history, we hope they will pause and reflect on the individuals who participated in this collective action. Just like George Mountfort and Ebenezer Jackson in the nineteenth century, today’s Tea Party descendants can honor and pass on their own family legacies, now 250 years after a group of revolutionaries destroyed tea in Boston Harbor, and forever altered the course of American history.

Kristin Harris is Research Coordinator at the Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum in Boston.

1 Samuel Bradlee Doggett, History of the Bradlee Family (Boston: Rockwell and Churchill, 1878), 14–15, 18.

2 Ibid., 18.

3 Francis S. Drake, Tea Leaves; Being a Collection of Letters and Documents Relating to the Shipment of Tea to the American Colonies in the Year 1773 (Boston: A. O. Crane, 1884), xcvii– xcvii.

4 Edmund F. Slafter to George Mountfort, April 18, 1872, George Mountfort application, American Ancestors Membership Applications, 1845–1900, AmericanAncestors.org.

5 Memorial Biographies of the New England Historic Genealogical Society, vol. VIII (American Ancestors: Boston, 1907), 177–178.

6 Joseph Mountfort listed his birth year as 1751 in his pension application.

7 George Mountfort, American Ancestors Membership Applications [note 3]. Joseph Mountfort is not listed in Benjamin Thatcher’s 1835 Traits of a Tea Party, but he does appear (as “Mountford” on p. cxxxvii) in Francis S. Drake’s 1884 Tea Leaves: “A cooper, on Prince Street, died in Pepperill [sic], Mass., May 11, 1838; aged eighty-eight.”

8 George Mountfort, American Ancestors Membership Applications [note 3], p. 3.

9 [Benjamin Bussey Thatcher], Traits of the Tea Party; Being a Memoir of George R. T. Hewes (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1835), 261–262.

10 Francis Jackson, A History of the Early Settlement of Newton, County of Middlesex, Massachusetts, from 1639 to 1800 (Boston: Stacy and Richardson, 1854), 180.

11 Alice F. and Bettina Jackson, Three Hundred Years American; the Epic of a Family from Seventeenth-century New England to Twentieth-century Midwest (Madison: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1951), 111.

12 Ibid., 185, 343–344.